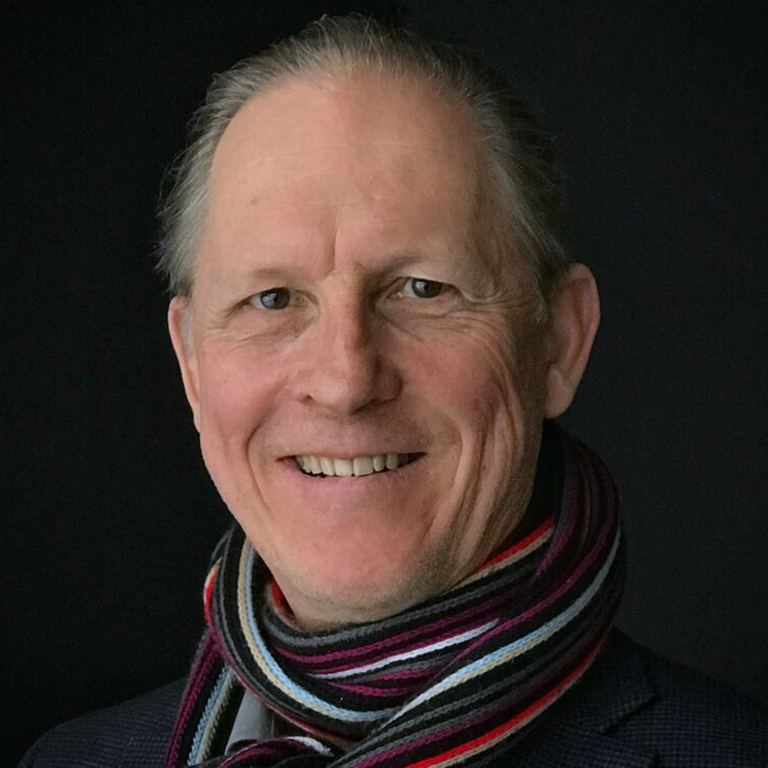

As director of the IU Food Institute, Carl Ipsen challenges us all to get real.

Historian Carl Ipsen, who helped found the Indiana University Food Project and the IU Food Institute in 2015, became their sole director last fall. Ipsen has focused on Italy for much of his academic career, exploring population policy in Fascist Italy and children’s issues in late-19th and early 20th-century Italy. An Italian edition of his 2016 book, Fumo: Italy’s Love Affair with the Cigarette, is due out this summer.

But an appreciation for food was literally in the air he breathed and the soil he stood on—in other words, he’s a Californian. Ipsen grew up in Berkeley and completed his undergraduate and graduate work at the University of California, Berkley.

“I worked for a decade at restaurants when I was a grad student,” he explains. “I’ve always had connections with restaurant people, winemakers, and olive-oil producers in California.” He did have one missed connection, however: he was turned down for a job at Chez Panisse, the cathedral of fresh, sustainable cuisine, located two miles from his Berkley home.

In 2012, when Ipsen was visiting the American Academy in Rome (where he’d been a fellow in 1998-99), he got a second chance to connect. Alice Waters, Chez Panisse’s founder, had been invited to Rome to revamp the Academy’s menu because its food was—in a word—terrible.

“To go live in Rome for a year and eat badly just doesn’t make sense,” says Ipsen. Waters had launched the Rome Sustainable Food Project, which provided what she calls “eco-gastronomic” food to the Academy.

In Rome, Waters promised she’d be a food cheerleader for Ipsen when he returned to Bloomington to work on like-minded projects. Over the next three years, Ipsen got busy. Among other projects, he worked with the IU Office of Sustainability, and he promoted the Real Food Challenge at IU.

The Real Food Challenge is a national, student-led, grassroots effort to encourage universities to buy real food—sustainable food that is locally or fairly produced, ecologically sound, or humane. IU students are currently collecting signatures on a petition to urge IU to commit to buying 25 percent real food by 2025. The most recent figures show that 6.8 percent of the food IU purchases in a year is “real.” While small, that figure is up from 3.7 percent the previous year.