The impetus for this course and installation began several years ago, when Lichtenstein and collaborators Phoebe Wolfskill, from the Departments of American Studies and African American and African Diaspora Studies (AAADS), and Rasul Mowatt, formerly from the Department of American Studies, wanted to create an exhibit that parallels the protest art exhibitions of the 1930s. At the time, these exhibitions were used to rally political support for anti-lynching legislation. As the anti-lynching message these works convey stays the same, they are also important commentary on what we choose to remember, what is not considered worthy of remembrance, as well as who remembers and who does not.

“The arts in the 1930s, like everything in the country in the 1930s,” said Lichtenstein, “became radicalized, so there’s a lot of protest art in that period. A lot of it, but not all of it, focusing on race. The anti-lynching artworks are just one strand of a ferment of the arts that became much more socially conscious in that period.”

In the course and as the installation opens for guests who have booked ahead of time, Lichtenstein noted that how to frame and show the art was something that he and his collaborators debated frequently.

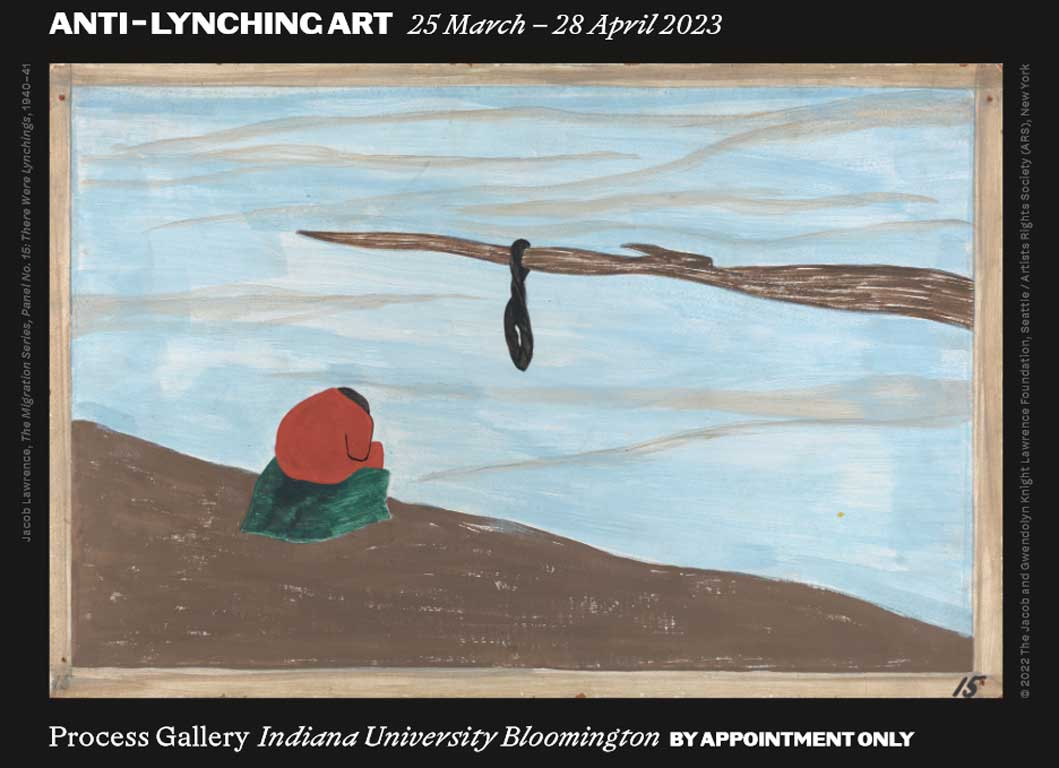

“One of the things we wrestled with – one of the things we continue to wrestle with – is on the one hand, it’s really important to show these works, to reveal the horror of lynching, and to show how it was protested in these artworks in the 1930s. At the same time, we’re very conscious of the fact that people don’t always like looking at these images. They’re upsetting. That’s why we’re very careful in all of our public-facing circulating material not to use that kind of image. But the exhibit has to include those,” he said.

Teaching an ugly history

Lichtenstein began his course description with a trigger warning for ASURE students who were thinking about signing up.

“I had a big disclaimer in the course description and on the syllabus,” he said, “that told students that taking this class means having to repeatedly look at these images. They had to know that. How they’ll respond to that I can’t say – everyone responds differently.”

Students worked with and used the artwork that is showcased in the installation and wrote image descriptions that would go with many of the works. While there is no way to become comfortable around these brutal materials, Lichtenstein made sure students were mentally prepared. They can also opt to create materials for the less graphic works that are displayed.

“It’s a really hard course to teach,” he explained, “because it’s about brutal, racist violence and white supremacy.”

As the students chose what works to write supplemental materials about, Lichtenstein learned that they were familiar with some of them already, including the one that he considers the most difficult piece.

“As I discovered, the most horrific of these images, the infamous photograph of the Marion [Indiana] lynching – everybody had seen it already. Every single student in the class had already seen it,” he said.

Throughout the semester, students learn about lynching through the lens of the politics of the 1930s, the NAACP, the Scottsboro case, the Marion, Indiana, lynching, and a comparative perspective of memory through other historical events. One of the primary learning outcomes of the course is that students will learn about contemporary community and national initiatives to memorialize victims of lynching and other forms of white supremacy and racist violence.

“The final part of our exhibit,” said Lichtenstein, “looks at these communal efforts at commemoration. The exhibit really tries to end on that, if not positive, then inspiring note.”

The exhibit: now and life after IU

Students have been preparing for the exhibit all semester in order to assist lead facilitators, and each student will co-host two tours each. The lead facilitators are “individuals who are working on racial reconciliation, public racial work, and memory work around the country,” Lichtenstein said.

After the exhibit is finished at IU, it has another life to live in Indianapolis. The exhibit will move to the Crispus Attucks Museum, which is attached to Crispus Attucks High School. Crispus Attucks High was opened in 1927 as a segregated school and now maintains an impressive museum with African American art and carefully curated exhibits for significant African American figures in American (as well as Indianapolis’s) history.

“Part of the exhibit highlights how communities in Indiana have been working to acknowledge and memorialize the victims of lynchings in their communities,” said Lichtenstein. “This has happened in Indianapolis, Terre Haute, and it’s happening in Marion.” It’s fitting that this exhibit will live in Indianapolis and continue to educate Hoosiers and visitors from farther afield.

This exhibit was made possible by funding from IU’s Arts and Humanities Council, the Platform Initiative for Indiana Studies funded by the Mellon Foundation, the College of Arts and Humanities Institute, IU’s Institute for Advanced Study, the Allen Whitehill Clowes Charitable Foundation, and the Eli Lilly and Company Foundation.